Metro Manila, Philippines — Fifty-two years ago, then President Ferdinand E. Marcos declared the Philippines under martial law. Candles are now lit every Sept. 21 as groups, advocates, and families of victims of human rights violations mourn a grim part in the nation’s history.

In the 2022 national elections, the Marcos’ dictatorship was heavily spotlighted in conversations, both online and offline, as the late dictator’s son Bongbong ran for the presidency.

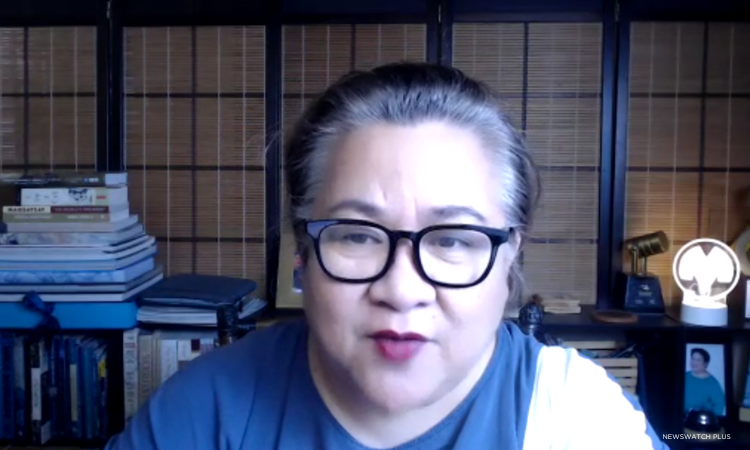

Mona Magno-Veluz, a content creator better known as Mighty Magulang, said the Martial Law years were “still very much misunderstood” on social media, even on TikTok, where many young people are users of the short-form video platform.

“I think we have a legacy of years of failure to educate the young on what Martial Law was about,” Magno-Veluz told NewsWatch Plus. “And what happened in that space was there was room for misinformation.”

Now, another Marcos is in power. Academics are trying to harness the interest of young Filipinos amid decades of sprawling misconceptions and false narratives on Martial Law.

Social media efforts

Filipinos have the highest social media time across the globe. It is not helpful that digital disinformation is widespread in the country. How can we counter this, especially the topic of Martial Law?

“We need the perspectives of different people para ma-triangulate ‘yung katotohanan [to triangulate the truth],” Magno-Veluz said.

Mona Magno-Veluz, a content creator better known as Mighty Magulang, shares her observations on social media, especially on TikTok. She says the Martial Law years are "still very much misunderstood."

“And that's what I try to do on social media. Talk about it, listen to how people understand certain events, and then try to inspire them to take the next step by reading more,” she said.

She also directs her social media content to what she said “level-headed individuals who are really there to learn.”

“And on TikTok, it's really all about making the conversation not a political topic but more like…a way for us to connect to a part of our past,” the content creator said. “It was very dark and we need to commemorate it.”

Josiah Quising, a co-founder of Project Gunita, said the academic research organization also conducts events, lectures, or talks about Martial Law to debunk myths. To gain traction, Quising said they chop portions of these activities into small videos for social media.

“There are of course memes, pub [materials], infographics, reels, TikTok [videos], but then again, ‘yun nga, it's still, it's really a difficult task,” Quising told NewsWatch Plus.

Survivors at the forefront

Magno-Veluz talks primarily about genealogy, history, and civics. She said it is helpful to highlight stories of those who lived through Martial Law to introduce that era of Philippine history.

Advocates and families of victims of human rights violations during the Marcos regime light candles at the Bantayog ng mga Bayani in Quezon City to mark the 52nd anniversary of the Martial Law declaration.

“I’m a Martial Law baby,” Magno-Veluz said. “And especially when I talk about the economics [of that time]...I was in college, it was actually happening. So I was studying it not as economic history, but as economic news.”

“That perspective alone, na sabihin mo na [that you tell them that] you were there and you were part of it, is one way of humanizing the effort,” she said.

She also highlights people “who exhibited civic responsibility during that time in our lives.” “Para sana [So that] we can start wanting more. We want to not make that happen again,” she added.

Students also appreciate learning Martial Law through the eyes of survivors, Quising said.

“We try to bring [the survivors] in,” he said. “We use our connections, our network, to bring these people closer to them, to reconnect the younger generation to the Martial Law generation, and to hear directly from them what really happened during the Martial Law era.”

Art as meeting point

Harvey Castillo teaches an elective course at the Ateneo De Manila University that introduces Martial Law through literature and film watching. He knows it is not without its challenges.

Why should we still study Martial Law? College instructor Havery Castillo lists three reasons: "Una, in a time where it is being erased, it is more important for us to study it and commemorate it. Ikalawa, ngayong ramdam pa rin natin 'yung actual na ramifications ng Martial Law, higit mahalagang i-trace natin 'yung current conditions natin sa ganitong 1970s Batas Militar. At ikatlo, the Marcosian playbook is still very much in effect. So, kaya napakahalagang aralin natin siya in order to detect it when it happens."

“May illusion na [There’s an illusion that] talking about this is an alien thing, that this is a thing or a topic that is divorced from our current realities,” Castillo told NewsWatch Plus.

The elective course is a deeper look into the dynamics of life during the Marcos regime, with theories on politics, sociology, and art complementing the discussions.

But many of the students just take the course as a second option, or when the favored subjects have already been filled up, Castillo said.

The instructor also said he sees an aversion to the topic of history or and intimidation to politics as among the struggles in reintroducing Martial Law in the academic space.

But Castillo maximizes the power of art. “Art is a really good common denominator ng ating lahat, tagpuan [to us, a meeting point], to talk about serious matters regarding our national and individual lives,” he said.

He also engaged college students to research media content under Bongbong’s presidency to make it more current. He said some students explore “Maid in Malacañang,” a 2022 fictional film retelling the last three days of the Marcoses in the Malacañang Palace before they flee to Hawaii during the 1986 People Power Revolution. They also look into the TikTok algorithm of the Marcos family.

“‘Yung film production nila ay pwedeng TikTok reels, na pwedeng YouTube short film,” he said. “So, ang isang effort na ginagawa ko ay lagi’t laging ilapit ‘yung kurso sa popular na media sa kasalukuyan nang sa gayon ay hindi maiwan sa Dekada ‘70 ang usapin ng batas militar at mailapit ito sa mga kabataan, sa Gen Z, sa Generation Alpha.”

[Translation: Their film production can be in the format of a TikTok reel and YouTube short film. My effort is to draw the course close to current popular media so that the topic of martial law will not be left in the 1970s and make it more relevant to the youth, the Gen Z, the Generation Alpha.]

The role of educators

Project Gunita was founded after the 2022 presidential elections. Quising said his organization has seen increasing interest to learn Martial Law history.

Aside from conducting events to debunk myths of Martial Law, Project Gunita is interested in archiving old books, newspapers, and magazines during that time in history. But co-founder Josiah Quising says the group has put its archival and digitization effort on hold due to limited resources.

“We've got a lot of invitations from different schools and we have organized, as well, different partnerships and different events towards that particular goal or objective,” he said.

Quising said their audiences are mostly students across all levels. What’s important, he said, is matching their interests to sustain their engagement in the activity.

But to drive more conversations is to help capacitate educators integrate the topic of Martial Law in their discussions across all subjects.

“We are trying to work on [developing] a course on how to teach Martial Law history para hindi lang kami ang nagtuturo nito [so that we are not the only ones teaching this],” Quising told NewsWatch Plus. “Hopefully, more teachers from different generations would have an interest and would have the necessary…materials on how to teach Martial Law history.”

Looking at the current basic education curriculum in the Philippines, the country’s history is now more focused at the elementary level. At junior high school, Araling Panlipunan teachers can tackle Martial Law in some lessons in Economics (Grade 9) and Contemporary Issues (Grade 10).

It becomes a significant task for teachers to teach Martial Law, and at the same time to facilitate discussions to help young Filipinos understand it’s not just a mere topic — it’s an actual time in history that happened just five decades ago.

“Alam kong ibang-iba talaga in dynamics kapag audience mo high school or elementary [The dynamics in high school or elementary are really different],” said Castillo, a college instructor. “You need to make the learning more digestible and accessible for them.”

Driving conversations

The late dictator Ferdinand E. Marcos, father of the incumbent President Bongbong Marcos. (File photo)

Castillo said there are many efforts to commemorate Martial Law in and out of academic communities. He hoped more students would be more involved.

“We were all oppressed and exploited, even if we have this illusion that we are divided as a nation,” he said. “It’s a smokescreen by power to make us feel that this is a divisive topic.”

“When in reality, if we go back to the root of it…We were more united than ever in our experiences of being exploited and oppressed,” the educator said.

For Quising, it’s also important for others to share what they learned about Martial Law through normal and casual conversations in a bid to correct propaganda and false narratives.

Content creator Magno-Veluz or “Mighty Magulang” also hoped both young and older students will revisit the topic of Martial Law.

“Not to drive any political agenda or to talk ill about those who have moved on, but really look at our gaps, our shortcomings as a nation, para hindi na maulit [so that it won't happen again],” she said.

“Talagang feel na feel ko ‘yong sinasabi nilang [I really feel what they’re saying], ‘Never again.’”