SM Book Nook sits in the middle of a working mall, but the pace inside it feels different. People drift in and stay longer than they meant to. A parent sits while waiting for a ride and ends up opening a book. Students pass through and grow quiet. A child pulls a book from a low shelf and settles on the floor as if the space had always been meant for them.

Shereen Sy watches this without interrupting it. She stands slightly to the side, listening more than she speaks, her attention moving from one small moment to another. When she answers, she pauses first, her left eyebrow lifting as she works through her thoughts. At first it can feel intimidating. Then it becomes clear she’s simply thinking carefully before she speaks. She doesn’t rush conversations and she doesn’t try to control how people use the space. She observes, and she prefers that the focus stays on the work rather than on her.

Shereen grew up in Singapore as an only child, surrounded by books that filled the quiet hours. “Reading was my companion,” she says. “Because I’m an only child, it became an escape. Like a partner.” She studied architecture in Australia, where she also met her husband, and later moved to Manila, into a country that felt familiar and unfamiliar at the same time, and into one of its most visible families. The transition wasn’t dramatic. It was slow and personal. She spent those early years raising her children, finding her rhythm, and watching how life unfolded around her.

Motherhood came first, and everything else followed from there.

Reading took on a different weight once she had children. It wasn’t just about what she loved anymore. It became about access, about environment, about meeting children where they are. Her daughter gravitated toward books easily. Her son didn’t.

“He wasn’t drawn to words at first,” she says. “So we tried graphics. Humor. That’s what worked.”

She saw early on that reading depends as much on environment as it does on interest. “Everybody’s a reader,” she says. “You just haven’t found the right book yet.”

Those years were filled with observation. Watching her children, watching other families, watching how people moved through the city. The malls stood out. People didn’t just shop there. They waited there, spent time there, brought their children there. Spaces existed where people lingered but didn’t stay, and she kept noticing what could be done differently.

In Singapore and Australia, where she studied and met her husband, reading had always been part of everyday life. Libraries didn’t feel intimidating and books were simply present. So when the question comes up about Book Nook being placed inside a mall, the instinctive answer feels almost obvious. Was it strategic, putting a reading space in what many consider the natural watering hole of Filipino life?

She laughs and shakes her head.

“There was no strategy at all,” she says. “It just made sense.”

People were already there. Families, students, workers between errands. The space didn’t need to be invented. It needed to be reimagined.

The conversation shifts to literacy and the way learning is spoken about in the family she married into. Education, she says, has always been seen as a way forward. “Education has always been the loophole out of poverty.” Reading sits at the center of that belief.

The Sy family has long advocated for learning, often without publicity. The partnership between SM Cares, the social development arm of SM, and the Autism Society Philippines is one example. It began after an incident involving a lost child inside a mall exposed how unprepared public spaces could be for situations involving children with special needs. Hans Sy, chairman of SM Prime Holdings, pushed for changes so the situation would never happen again, and from there the work expanded into training, awareness, and support systems designed to make spaces more responsive and inclusive.

It isn’t widely talked about. It doesn’t need to be.

Book Nook grew from that same way of thinking. It didn’t start as a grand program. It began with a simple idea: a place where reading could exist naturally, inside a space people already used. Shelves were added, seating adjusted, books donated, and people began to stay. Authors started launching their books there without cost, grateful for a space that welcomed them without barriers. Families returned. Students lingered. Community groups asked to use the space.

Managing it isn’t simple. Each branch has its own personality, its own community, its own needs. Programs shift. Feedback comes in constantly. There’s always something that requires attention.

She smiles when she talks about it, half amused, half tired.

“It’s like birthing a child,” she says. “And then raising it.”

The work doesn’t end once the space exists. It grows and demands care in ways that feel familiar to anyone who has built something from the ground up.

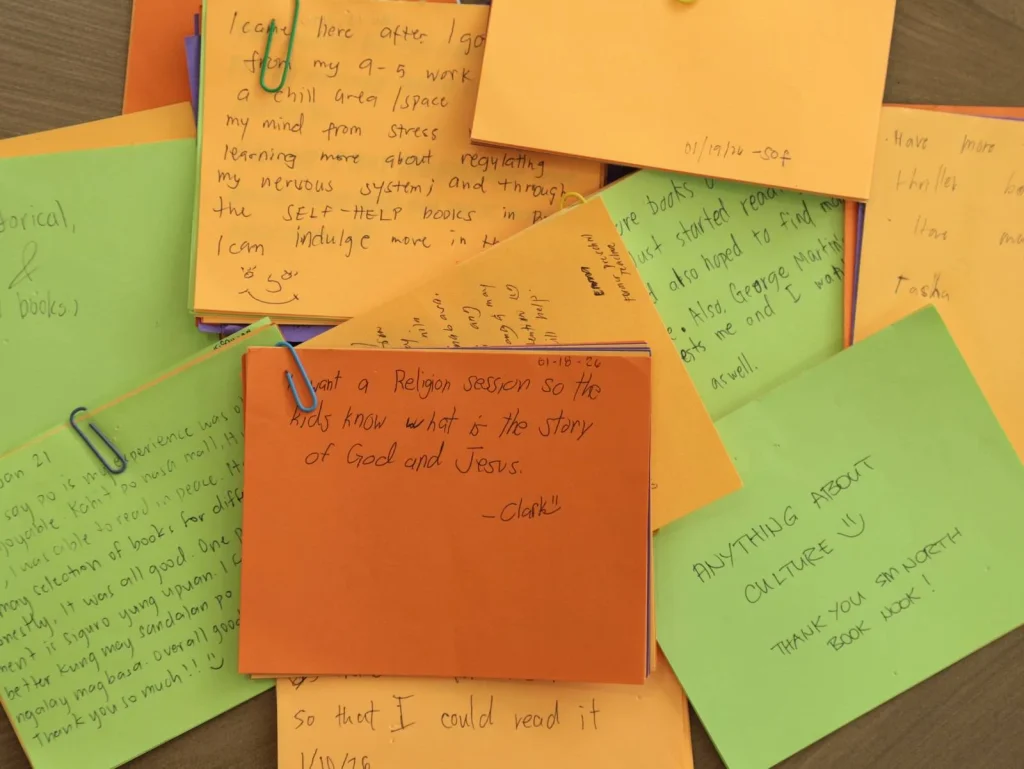

When the question turns to what keeps her going, she reaches into her bag and pulls out a stack of colorful handwritten notes. They’re messages from different branches, from visitors, parents, volunteers, and staff who spend time in the spaces and want to say what they mean to them.

“I bring them home,” she says. “I read them again. Slowly.”

She flips through them briefly. Some ask about specific books. Others simply say thank you. Many talk about how the space has given their children somewhere to stay, somewhere to sit, somewhere to read without being told to leave.

Tucked between the notes is a sheet of stickers.

She looks up and says, “It’s for your child. They mentioned you have one.”

The gesture is casual, almost automatic, but it’s hard to miss what it says about her.. The same level of care shows up in how she runs Book Nook. Nothing feels rushed. Nothing feels detached. Every decision seems rooted in how someone might experience the space, especially a child, especially a parent trying to make something meaningful out of an ordinary afternoon.

Other malls have started building reading spaces of their own, and the idea has spread further than she expected. Her team flagged it early, unsure how she would react. She didn’t see it as a threat.

“If more people are reading,” she says, “then that’s already a win.”

Ownership was never the point.

Shereen doesn’t talk about Book Nook like an achievement. There’s no sense of arrival in her voice. It feels more like something she continues to care for, something that now belongs to the communities using it. Parents stop by after meals. Students pass through between classes. Children sit on the floor and read. Writers gather. Conversations unfold.

The space lives its own life, and she stays close without needing to be at the center, stepping in when needed and stepping back when it’s not.

Every chapter of her life led here, from growing up with books, to studying how people move through space, to moving countries, becoming a mother, starting over, and building slowly from observation. Motherhood sits quietly at the center of it all, guiding how she cares for what she builds and how she allows others to make it their own.