Palm Beach, Florida/Washington, US – US President Donald Trump’s decision to attack Venezuela, arrest its president, and temporarily run the country marks a striking departure for a politician who long criticized others for overreaching on foreign affairs and vowed to avoid foreign entanglements.

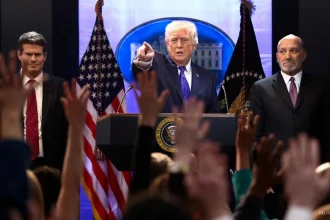

His vision for U.S. involvement in Venezuela, sketched out in a midday news conference, left open the possibility of more military action, ongoing involvement in that nation’s politics and oil industry and “boots on the ground.” The term suggests military deployment of the sort that presidents often avoid for fear of provoking domestic political backlash.

“We are going to run the country until such time as we can do a safe, proper, and judicious transition,” Trump said.

He gave little sense of how far he was willing to go to gain control of Venezuela, where Maduro’s top aides appeared to be still in power.

‘The wars we never get into’

As recently as his inauguration for a second term last January, Trump told supporters: “We will measure our success not only by the battles we win, but also by the wars that we end, and perhaps most importantly, by the wars we never get into.”

Since then, Trump has bombed targets in Syria, Iraq, Iran, Nigeria, Yemen, and Somalia, blown up dozens of alleged drug boats in the Caribbean Sea and Pacific Ocean and made veiled threats to invade Greenland and Panama.

The overnight attack on Venezuela was his most aggressive foreign military action yet, striking the capital Caracas and other parts of the country and capturing Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro and his wife to face drug-trafficking charges in New York.

These developments ran counter to some Republican hopes that the president would focus more on voters’ domestic concerns – affordability, health care and the economy.

Trump told the news conference that intervening in Venezuela was in line with his “America First” policy.

“We want to surround ourselves with good neighbors. We want to surround ourself with stability. We want to surround ourself with energy,” he said, referring to Venezuela’s oil reserves.

But the emerging political stakes were captured by a social media post from U.S. Representative Marjorie Taylor Greene, a Georgia Republican, who has broken with Trump because of what she said has been his departure from the America First rhetoric of limiting foreign adventures. She is resigning from Congress next week.

“This is what many in MAGA thought they voted to end. Boy were we wrong.”

Risk of quagmire

Trump’s ongoing attention to foreign affairs provides fuel for Democrats to criticize Trump ahead of midterm congressional elections in November, when control of both houses of Congress is likely to turn on just a few races across the United States. Republicans narrowly control both right now, giving the president a largely free hand to enact his agenda.

“Let me be clear, Maduro is an illegitimate dictator, but launching military action without congressional authorization, without a federal plan for what comes next, is reckless,” Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer said in a call with reporters.

Trump has worked to end several foreign conflicts, including in Ukraine and Gaza, while lobbying for a Nobel Peace Prize. But U.S. military actions tend to draw more public attention and historically have carried more political risk for presidents and their parties.

Polls have shown that, before the attack, the prospect of U.S. military action in Venezuela was unpopular, with roughly one out of five Americans supporting force to depose Maduro, according to a November Reuters/Ipsos survey.

Republican debate over foreign policy

Trump’s top diplomat and national security adviser Marco Rubio called several members of Congress early on Saturday in an effort to blunt opposition to military action.

Mike Lee, a prominent libertarian-leaning senator, initially questioned the administration taking military action without a declaration of war or authorization for the use of military force, but wrote on X he concluded that the operation likely fell within the president’s authority after speaking to Rubio.

Republican Representative Thomas Massie, a frequent Trump critic, wrote in a post on X that Trump’s warning of further strikes on Venezuela “Doesn’t seem the least bit consistent” with Rubio’s characterization to Lee. “If this action were constitutionally sound, the Attorney General wouldn’t be tweeting that they’ve arrested the President of a sovereign country and his wife for possessing guns in violation of a 1934 U.S. firearm law,” Massie wrote in a separate post.

US ‘will get tangled up’

For a president who has consistently contrasted himself with the Republican “neoconservatives” of the late 20th century, Trump’s foreign policy has developed striking similarities with that of his predecessors.

In 1983, under former President Ronald Reagan, the U.S. invaded Grenada, claiming that the government at that time was illegitimate, a claim Trump has also made with respect to Maduro.

In 1989, former President George H.W. Bush invaded Panama to depose dictator Manuel Noriega who, like Maduro, was wanted on U.S. drug-trafficking charges. In that case, the U.S. installed Noriega’s replacement.

Elliott Abrams, who served as Venezuela envoy in Trump’s first term, said he did not believe the president was running a political risk at home in ousting Maduro and that he “has a lot of latitude as long as American troops are not dying.” But he acknowledged: “I don’t know what running Venezuela means.”

“He’s done the right thing in removing Maduro,” said Abrams, a senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations think-tank. “The question is whether he will do the right thing in supporting democracy in Venezuela.”

Brett Bruen, a former foreign policy adviser in Barack Obama’s administration, said the U.S. could now be sucked into overseeing a complex transition process.

“I don’t see any short version of this story,” said Bruen, now head of the Global Situation Room, an international affairs consultancy. “The U.S. will get tangled up in Venezuela but will also have new problems to contend with related to its neighbors.”